In the sun-drenched land of the Nile, where the ancient Egyptian civilization thrived for millennia, art was never created for art’s sake. Every line etched into stone, every posture of a statue, and every chosen material spoke a language of profound symbolism. In ancient Egypt, statues were not mere decorative objects; they were sacred vessels, serving as intermediaries between the human and the divine.

This article explores the symbolic meaning behind Egyptian statues, their historical context, and how these artworks reflected the Egyptians’ complex understanding of power, spirituality, and immortality.

The Function of Statues in Ancient Egypt

To the ancient Egyptians, statues were more than representations—they were animated presences. Known as ka statues, many were created to house the soul (ka) of the deceased, particularly for kings and high officials. This belief was deeply rooted in their spiritual ideology: while the physical body decayed, the ka could live on through an enduring image.

Temples were filled with statues of gods and pharaohs not only to glorify them but also to provide a medium through which the deities could receive offerings and prayers. These sculptures had specific roles—to be worshipped, to protect sacred spaces, and to symbolically maintain order (ma’at) in the universe.

Materials as Symbolic Choices

The materials used in Egyptian statues were chosen with intent, each imbued with meaning:

Limestone and Sandstone: Common and local, these stones were used for statues intended for tombs and temples, symbolizing endurance and stability.

Granite and Diorite: Dense, dark, and difficult to carve, these stones symbolized eternal strength and divine protection. Statues of gods and pharaohs made from granite were meant to last forever.

Gold and Electrum: Rarely used for full statues, but often inlays or masks (like Tutankhamun’s famous mask), gold symbolized the flesh of the gods—shining, eternal, incorruptible.

By combining form with substance, artists aligned the physical characteristics of statues with spiritual aspirations.

Pose and Proportion: Codifying Power and Divinity

Egyptian statues are known for their formal, rigid poses—this was no artistic limitation but a visual code of stability, eternity, and divine order. The most common positions include:

Standing with one foot forward: Denotes life and readiness, commonly seen in pharaonic statues.

Seated with hands on knees: A dignified, eternal posture often used for deities and officials.

Cross-legged or kneeling: Positions of reverence and humility, often used for offering bearers or priests.

Proportions were governed by strict canons. Grid systems ensured that each figure adhered to divine harmony. The head, torso, and legs followed predetermined ratios to symbolize perfection and divine alignment.

The Pharaoh as Divine Statue

Pharaohs were not just rulers; they were living gods. Statues of pharaohs were deliberately idealized—youthful, muscular, calm, and symmetrical—to communicate eternal authority. These depictions were not portraits but divine archetypes, reinforcing the ruler’s sacred role as mediator between gods and people.

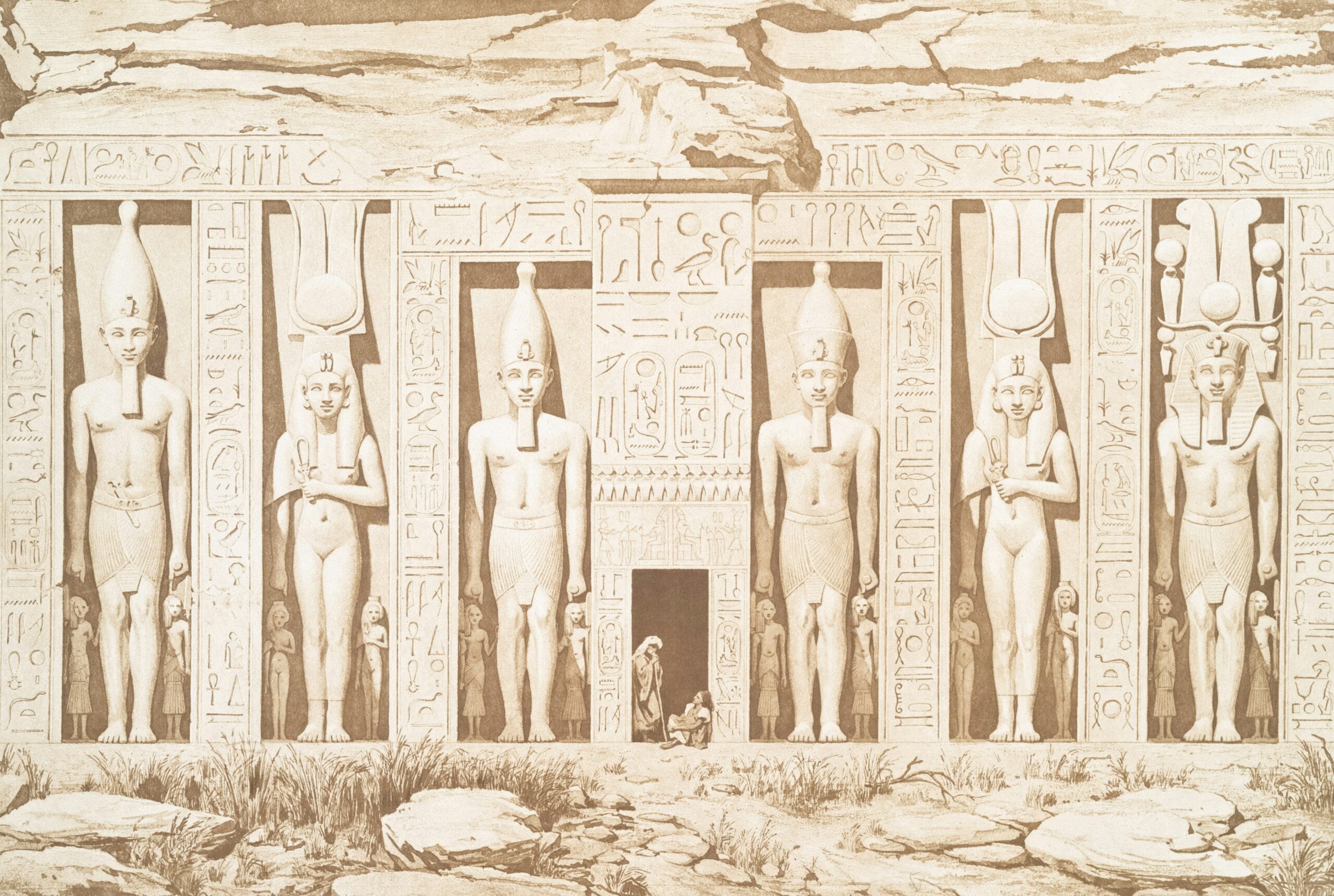

Colossal statues, such as those at Abu Simbel, were designed not just to awe viewers, but to project divine power across space and time. The enormous scale signified the eternal might of the pharaoh, even in death.

Symbolism in Iconography

Egyptian statues included a wealth of symbolic details:

Headdresses and Crowns: Indicated divine or royal status—like the double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt or the nemes headcloth.

Ankh: The symbol of life, often held in the hand.

Was Scepter: A symbol of power and dominion.

Scarab and Falcon Motifs: Representing rebirth and the god Horus, respectively.

The deliberate inclusion of these elements ensured that the statue conveyed not just identity, but sacred authority.

Statues in Tombs: A Path to Immortality

Tombs of the elite were filled with statues, often in groups representing family members, servants, and scribes. These images were more than commemorative—they were designed to provide the deceased with a functioning afterlife. Servant statues (shabtis) would magically labor in the Field of Reeds on behalf of the dead, while family statues ensured eternal companionship.

In royal tombs, statues helped secure the king’s continued rulership in the afterlife, solidifying the eternal cycle of death and rebirth.

Enduring Influence on Art and Culture

The artistic conventions and symbolic depth of Egyptian statuary influenced Greek, Roman, and even modern sculpture. The emphasis on formality, monumentality, and the use of art as a sacred language continues to inspire artists and historians today.

Contemporary sculptors still look to ancient Egypt for inspiration—learning how form can embody philosophy, how symbolism can enrich material, and how art can transcend mortality.

Conclusion

In ancient Egyptian culture, statues were not lifeless stones; they were charged with spiritual significance, embodying gods, kings, and cosmic order. Their design was deliberate, their materials sacred, and their meaning profound. As we study these eternal guardians, we gain not only insight into an ancient civilization but also a deeper understanding of how art can bridge the mortal and the divine.